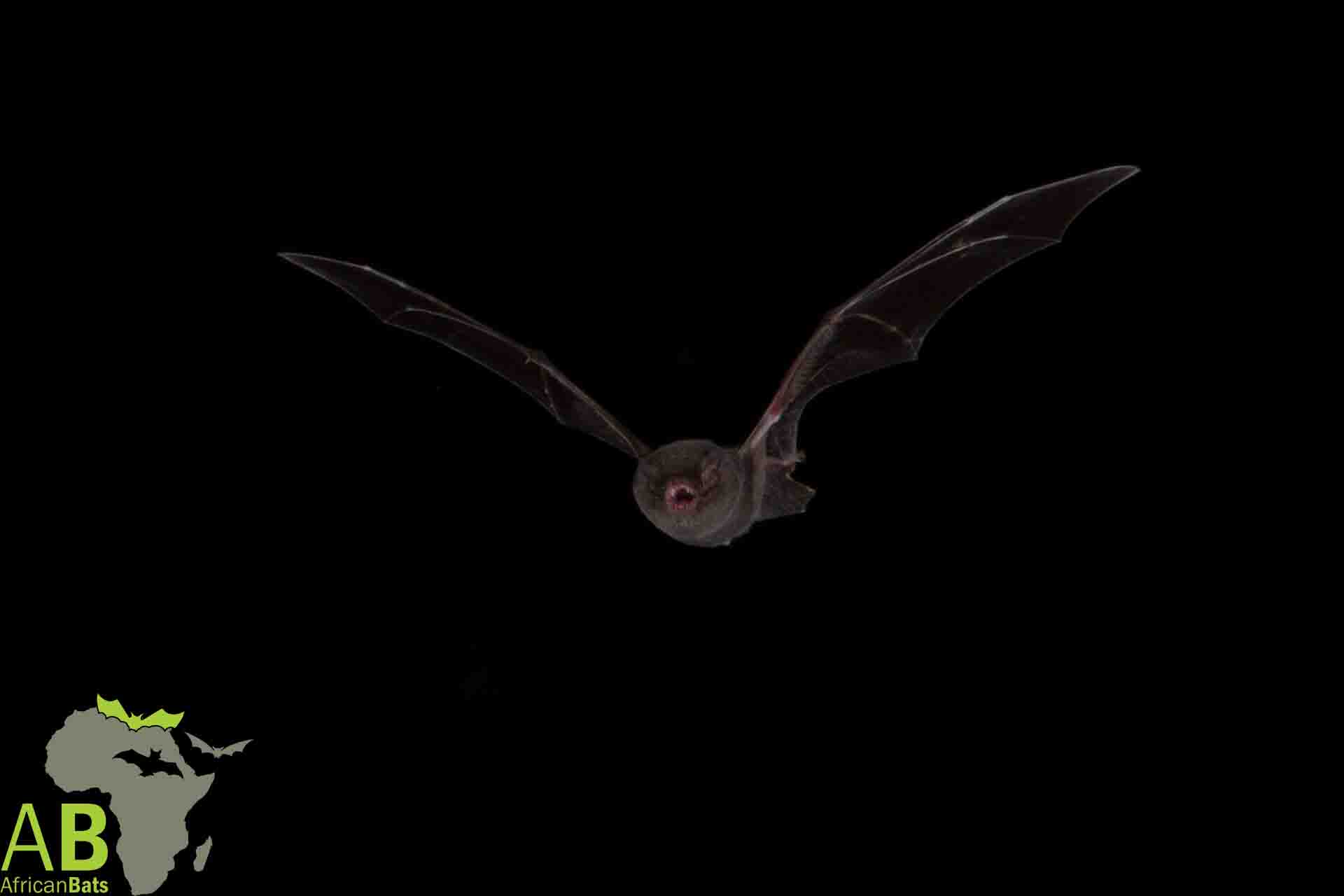

AfricanBats NPC in collaboration with the University of Pretoria and Ditsong National Museum of Natural History, are embarking on various long-term projects to assess and monitor the caves and the bat species that use them. The area surrounding the Hoogland Health Hydro has a number of caves of interest. During a recent acoustic survey, five cave dwelling and four non-cave dwelling bat species were detected.

Hoogland Health Hydro has one species of international concern; the Natal Long-fingered bat (Miniopterus natalensis) which is listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS). Next week (23rd October) the 12th Conference of Parties is meeting in the Philippians to discuss progress and way forward with regards to migratory species. South Africa can be proud of what it has been able to achieve over the past 4 years, to protect migratory fish, marine mammals and birds –bats nothing to report (see page 44, http://www.cms.int/en/document/south-africa-national-report-cop12). For the next 13 COP meeting in 2021, AfricanBats aims to assist South Africa or any southern African country to put forward a draft African Bats Agreement with the support of the Southern African Developing Countries (SADC) – to focus efforts to build partnerships with landowners who are custodians of caves across southern Africa.

AfricanBats 2017 intern (Ms Mariette Pretorius), plans to tackle various questions around land use and space use of cave bats for her PhD (2018-2020). The Natal Long-fingered bat being the primary focus, used as an ‘umbrella species’, to conserve other cave-dwelling bats that use the same caves. AfricanBats together with the University of Pretoria have obtained all necessary ethical clearenece and permits to start implanting small tags (similar to the microchip used in pets)– our target is to tag 500 bats (out of a population of 300,000) by end February 2018.

If all goes according to plan and grants are successful we hope to have in South Africa at least one cable reader system. This system works similar to the scanners set at most shop doors – where if you have not removed the tag – the alarm system goes off. As the tagged bat flies through the area of the reader – the unique tag number is recorded – providing us with who, where and when. This cable reader system will be moved to different cave entrances across the Highveld during April and May. These caves sampled again in September – October (after the hibernation period), see who may have been at one cave at the start of the winter, but then by the end of winter has moved. During the September/October field work at the caves bats will be caught and additional bats from these multiple caves across the Highveld tagged. Late October/November (bats known to leave the Highveld caves and migrate to warmer caves to give birth to young. With additional cable reader systems, additional caves within South Africa and in neighbouring countries may be monitored to establish connections between the caves used by these bats. If we can prove movement across international boundaries – then this strengthens the case for the development of an African Bat Agreement for migratory species. Nevertheless, even if our data does not support populations crossing international boundaries – this information is still critical for the development of species management plans.

Bats are long-lived animals, with a record from South Africa for the Natal Long-fingered bat of 18 year been reported and in Europe its sister species at 38 years. The passive reader will allow us to monitor bats at and during sensitive times of the year, without the need to capture the individuals, providing valuable information about these species life histories.

Other than monitoring the individual bats, Hoogland Health Hydo will form part of a network of protected areas, where long-term bat detector stations are established. Not all bat species can be identified by echolocation call. However, a few species in localized area this is possible. This network of bat detector stations both within and outside formal protected areas – will provide us with key information about the relative population trends and status of various species over time. We expect that in areas with increased urbanization and development, we will find more of the non-cave dwelling bats, who compete with the cave-dwelling species for food (insects), reducing their numbers. This information will feed into a Southern African National Bat Status Report, used by the IUCN and other International Conservation organizations – especially if we can roll out this type of monitoring in all countries who sign the African Bats Agreement. More importantly is to develop a network between the custodians of these caves (landowners), who are on the ground to protect these sites –with or without the support of their governments– but it always nice to have their support and backing.